Healthy Mama, Healthy Baby

Where in the world will you have your baby? It’s a question you probably haven’t considered, but for millions of women around the globe, it makes all the difference.

Sweden: a mother chooses a home birth for her second child. The chance that she may die in childbirth is low—a mere 1 in 11,400.

India: a poor mother delivers for the first time in a newly thriving private hospital, a social business serving her community. She is lucky to deliver with skilled care in a country where the maternal mortality rate is 1 in 140.[1]

Niger, Africa: a teenage girl suffers a catastrophic hemorrhage during her labor. She’s over a hundred kilometers from the nearest health facility. Her lifetime risk of dying in pregnancy and childbirth is 1 in 7.[2]

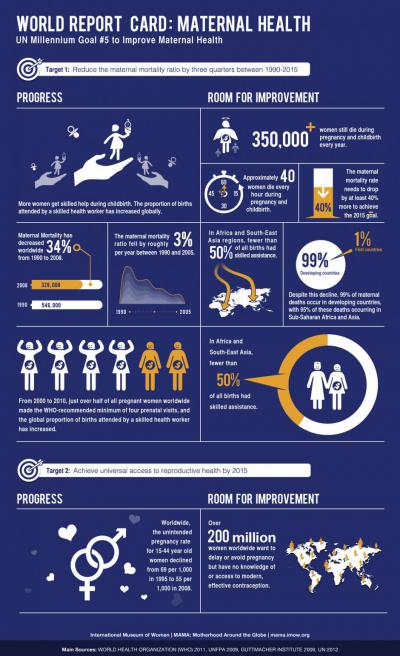

While women in Norway live in the safest place in the world to give birth, those in Afghanistan are living in the most dangerous.[3]. The United States’ rate of maternal mortality is the highest of any industrialized nation, and African American women are nearly four times more likely to die than white women.[4]

For many families, childbirth is a miraculous occasion; for others, it’s a tragedy. For women in countries where the birth of a girl is seen as a misfortune rather than a blessing, the well-being of both the mother and child can be endangered from the time the baby's sex is known. In India and China, among families that can afford it, it is common to use ultrasound to determine the sex of the child and then to abort the female foetus.

If you’re pregnant, you may experience a complication, no matter who you are or where you live. But the odds of suffering a life-threatening emergency are infinitely greater if you are a poor woman living in a marginalized community in a developing nation.

Many factors influence what makes a place safe for a woman to give birth – from the immediate and practical, such as access to affordable, skilled healthcare before and after birth – to social, economic, and cultural factors. Such factors include the status and education of women and girls in society, their relative power within the home, their safety and security in the workplace, and the support they get from either their employer of government to prepare for and recover from birth.

A woman's survival rate, and that of her child, also depends on overcoming three critical delays:

- Delays in seeking care--in many countries, girls and women are not considered worthy of medical attention, and birth remains within the realm of traditional attendants

- Delays in reaching an emergency care facility--often the barriers are practical. Few rural women have access to a local doctor or medical facility, road conditions are poor, and poverty makes it impossible to afford transport

- Delays in receiving care--poor people are often overlooked or can't afford bribes to get access to medical facilities, or facilities may lack adequate staff, equipment, or supplies.[5]

The poorer you are, the worse the chances of you or your newborn making it through childbirth safely. But thanks to organizations such as the White Ribbon Alliance and other dedicated maternal health advocates, there is hope for mothers everywhere. In Bangladesh, for example, maternal deaths have dropped by 40% in less than ten years as more women gain access to emergency care and family planning.[6] Women’s empowerment, economic opportunities, community mobilization and the media are all helping drive change.[7]

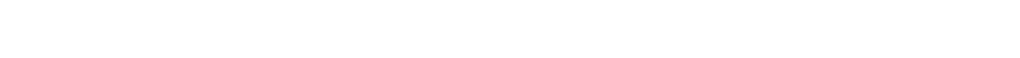

Maternal health advocates had a big win with the UN’s 2010 announcement that, for the first time in two decades, deaths in pregnancy and childbirth dropped by one-third.

Despite this progress, however, most high mortality countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia will not meet UN Millennium Development Goal 5, which aims to cut maternal deaths by 75% from 1990 to 2015 and achieve universal access to reproductive health[8].

So what’s needed now? Training of 350,000 additional midwives, investments in family planning, HIV counseling and high-quality emergency care accessible to women in marginalized communities, where mortality is highest, and a unified global movement of women who demand action from their political representatives.

Women are watching, and demanding, that politicians deliver on their commitments.[9]

In the Healthy Mama, Healthy Baby gallery:

- LISTEN to Mamas Voices, and hear what women all over the world have to say about their experience of pregnancy and childbirth

- CONSIDER Christy Turlington-Burns' essay about how we can only make progress in maternal health by prioritizing mothers

- ENGAGE WITH Renee Hoffman's art piece "Cesarean Quilt," about how she used a creative outlet to deal with the pain of her traumatic labor and delivery.

- AND MUCH MORE >

[1] State of the World’s Mothers 2011, Accessed 20 November 2011

[2] AMDD, Averting Maternal Death and Disability, Accessed 27 October 2011

[3] Afghan mothers at risk, Al Jazeera Television, Accessed 28 October 2011

[4] Maternal Health in the U.S., Amnesty International, Accessed 27 October 2011

[5] Maternal Health Facts, Women Deliver, Accessed 27 October 2011

[6] Maternal deaths in Bangladesh reduce by 40% in less than ten years, USAID Impact Blog, Accessed 20 November 2011

[7] Back to Bangladesh - Day 1 - June 20, 2011, Blog post by Christy Burlington Burns, Accessed 20 November 2011

[8] Lack of Skilled Birth Care Costs 2 Million Lives Each Year, Report Shows Both Mothers and Newborns at Risk, Accessed 20 November 2011

[9] Women Deliver, Accessed 8 November 2011