Additional Stories

Waiting to Share

It's May and the sun tilts toward me. Longer days too; that premature shutting down of winter doesn't come. There is a cold wind though; I can see it through the window, bouncing the pink petals on the trees. I spend the mornings in bed to put off that first standing up which makes me nauseous. The doctor says I should try eating a cracker before I get up, but it doesn’t work. I walk to the bathroom and I'm sick in the basin. White froth and then with further retches it turns smooth and dark yellow like cough medicine, only bitter. Then back into bed sweaty and hungry.

Saif’s been away eight days and nine hours. He’s not due back until next week. I can't phone him unless there's an emergency. They don't like personal phone calls on the oil rigs and he's not allowed to take his mobile phone because it’s against the regulations. I’m floppy without him. He is excited and confident about the baby while I wade through the days. Tomorrow I go to my first ultrasound appointment at the hospital. Husband offshore, parents in another country, not a single friend to accompany me.

I thought pregnancy meant radiant skin and a stomach to be proud of. But I am barely showing and held back by waves of sleep; anxieties about the baby, about the birth, about the world I hear about on the news. Whenever Saif comes home we dwell on the changes in my body. Only a swell below my navel but my breasts are bigger. Sometimes they hurt, a dull pleasant ache, a gradual heaviness.

Hunger like I have never experienced. I stare at the ceiling and know that, if necessary, I can fight someone for food and I can rummage through garbage looking for tidbits. It is something I did not know about myself. The baby is a parasite, the pregnancy book says, the baby will take from you all that he needs. Well, the baby seems to need eggs with ketchup, beans with ketchup, crisps with ketchup… so this is what a craving is, I realize, this passion for tomatoes, their redness, their tangy taste. Yesterday it was stale bread with ketchup, and when the bread ran out, just one spoonful after the other.

This is the most difficult challenge, getting out of bed. Not getting up to vomit and coming back but getting up to have a shower and dress. If I am going to cry it will be now, first thing in the morning with the nausea in my chest and the day stretching out ahead.

It’s not fair, is it, that Saif has taken me away from my career, my friends, my family and brought me here only to leave me and go offshore? But I am being irrational. It is his work and I should be supportive. I had walked into this marriage with eagerness, with eyes wide open. My parents were becoming stifling, my friends boring and my womb, fertile and unattended, was eager to flourish and enclose. I did not want to sink into my thirties, to reach the desperate stage and acquire that expectant stalking look.

Saif was the nicest of them all, fresh and honest in an irresistible way. Marriage was a good move, coming here the right choice. It’s not a raw deal; it’s actually a good package. Yes, the bad weather, the loneliness when Saif goes off-shore but when he is here it is like a holiday; one honeymoon after the other. In the two weeks that he is onshore we stay up late, we have breakfast at lunchtime, we go to the cinema, we go out shopping. It is nice to be able to afford things, not to have to skimp and save. He is generous really, when he is freezing on the wretched rig working night shifts he keeps himself going by repeating, ‘Think of the bonus, think of the baby, think of the bonus.’ I have a lot to thank Allah for, instead of crying.

I bribe myself with breakfast so that I can get through the shower. I toast bread and make an omelette with feta cheese and the necessary tomatoes. I put more tomatoes than eggs, more tomatoes than cheese. It is mysterious, this craving, too intense to be explained away by a need for vitamin C. Even the pregnancy books are unsure. They say it is hormones that will only settle at fourteen weeks but that doesn’t explain why I have suddenly gone off coffee and can’t live without tomato juice.

The post brings more rejection letters. All the job applications I sent out when I first moved here are bouncing back. But do I have the audacity to turn up at an interview pregnant? These days I am sick or asleep, restless for a specific taste, hiding from toxic scents real and imaginary. I clean the bathroom with ordinary soap to avoid detergents; in the supermarket I bypass certain rows.

I drive to the kebab shop for lunch. Driving is a triumph for me, a reminder that I am not completely helpless, completely housebound. It is a throwback to my past single life, the career woman with the little car, with somewhere to go, very busy. In another part of the world I had been a social worker. I identified children at risk and set up a programme to rehabilitate teenage drug addicts. I have to stop the car and vomit in a paper cup. Nothing comes out but white froth, my breakfast has fast disappeared. It is an empty stomach than makes me sick, though it is hard to believe. When I am full, the nausea goes away. But I am digesting too fast. I can hardly hold myself back between one meal and the next. Traffic whizzes past me. I wipe my mouth with tissues and stuff them in the paper cup. It suddenly feels too warm in the car, I open the window, indicate and drive out.

The smell of the shop pleases me. I need the large kebab sandwich, the salad soaked in chili. I ask for ketchup too. Ketchup on the tomatoes, ketchup soaking the bread and the meat. It runs down the side of my mouth. A slim woman pushes her way through the door. It rattles so hard that most of us look up. Her deranged hair is streaked blonde, her nose bruised red; she is not steady on her feet. She stands at the door trembling. “Marouf,” she hisses. "Marouf" The youngest of the staff, handsome enough for Bollywood, rushes to her side, tries to lead her by the arm out to the street. She holds her ground, “You lied to me. You did ... You told me you’d be back, you told me … Come home…” She’s whining now and the rest of the staff are hiding their sniggers.

Marouf’s face is dark with embarrassment. He tilts his head and squeezes her arm. His voice is too low for me to hear his replies. She starts to hurl abuse at him, one ek sound after the other. When he tries to push her out the door she cuffs his face. This relieves her momentarily and he is able to dislodge her into the street. The door clinks behind them. I squeeze more ketchup onto my salad. I finish my sandwich and my drink. Marouf comes back in and his workmates taunt him in a language I don’t understand. The ketchup has run all over my plate and I don’t have a spoon to lap it all up.

No longer hungry, I feel fine. The fresh air is doing me good. I hurry past Starbucks, the merest whiff of coffee threatens a nausea attack. Strange that I used to malfunction without two black coffees a day, now how to explain this sensitivity to smells? The foetus protecting itself from the dangers of coffee is a proposition but then not every pregnant woman has the same response.

I walk into a mother-and-baby store and wish that it wasn’t too early to buy maternity clothes. I touch the baby products. Soft yellows and blues and pink. Cuddly toys, terry cloth; cots and bubble bath. I pick up a bottle of baby oil and breathe in the scent. It fills me with wellness, with innocence; baby sweetness and joy. The baby clothes for girls are nicer than the ones for boys. This time tomorrow, after the ultrasound, will I know if my baby is a he or a she? I can’t want a boy or want a girl, it is already predetermined, it is already, thrillingly, too late. I am carrying a brand new creation, a beauty to cuddle, a precious name, a fresh personality whose steps I will share. Next to me a woman, about eight months pregnant, is looking at the plastic baths. Her stomach is like a basket ball that had fallen once on her lap, her navel is inside out, protruding against her T-shirt. I feel like I am in primary school looking up in awe at one of the senior girls. I buy vitamins and a cream for stretch marks. I buy two new bras. Saif will want to check out the car seat and the stroller. He will revel in all the baby gadgets, locks and mobiles--I smile thinking we will come here together.

Outside, I find myself face to face with the woman from the kebab shop. This time she is pushing a toddler in a pushchair and staring into the shop window. The little boy’s hair is so long that the fringe is almost covering his eyes. She must have left him outside the shop, I realize, he must have been all alone on the pavement all the time she and Marouf were having their fight! The baby sits straight up clutching his foot with one hand and a packet of crisps in the other; some of it falls to the ground.

It is because of him that I speak to her. “I saw you back at the kebab shop. Are you all right now?’ I bend to smile at her son. He looks at me and makes a lovely ba sound, his own distinctive voice, his few teeth sitting lonely in their gums. I want to lift him up, to bathe him, to feed him, to teach him. I am yearning for my own baby and my silent invisible swell of a stomach is a solemn promise, the secret I am waiting to share. Beyond the fog of lethargy and nausea, after the heaviness and the pain, I will look down at an infant in my arms. She will be the centre of my life, she will be in focus, in colour and everything around her will be blurred, in black and white. I reach out to touch the toddler’s hair. It is so pale that it is almost white. Surely he is too fair to be Marouf’s. Surely. I am judging his mother now and as if she can read my mind, she withdraws, her face grim. Without a word, she yanks the pushchair so that the poor child is jerked back into his seat.

“Wait,” I say but she is walking faster. I catch up with her and she is forced to stop. My words come out in a rush, “You should give him a rusk or a piece of fruit, not this snack that is not even potatoes! Get him something good. He needs proper food to grow. And cut his fringe, he can barely see through it…”

“I don’t need you interfering! Mind your own bloody business.” She pushes down on the handlebars so that the pushchair jerks up and comes down on my toes. I stand rooted to the pain as she flounces off. And because I haven’t spoken to anyone for days, I feel sorry for myself. I wipe my tears and hobble to the car. I used to have a gaggle of friends and invitations to parties; at work others listened when I made presentations, I even had an assistant in my last few months before I resigned. In that other past life, I never craved tomatoes and I must have passed one hard-done-by mother after the other without turning a hair.

Saif is getting out of a taxi just as I am parking my car. It is such a surprise that I almost bump the curb and forget to undo my seat belt. "Careful," he calls out as he lifts his rig bag from the boot and pays off the taxi. He is smiling and tousled like he always is when he first comes home, still with the noise of the machines ringing in his ears, the unsteadiness of the platform, the stinging wind of the North Sea. Now he can put all this behind him and have everything he’s been looking forward to. How perfect of him to be here today! I need the weight of his arms, his voice telling me off, his fingers rummaging through the things I just bought. I run into his arms. He explains that there’s been a false alarm at the rig and nonessential staff for the ongoing operation were evacuated as a precaution. Lucky for me he was one of them. He is still in his rig coveralls and the smell of the oil pushes its way up my nose, black grease down my throat, fumes in my gullet. I move my face as a burp turns into a gag, into a retch.

“What’s wrong?” He holds me but I twist away. I stagger to the side of the road and aim my mouth at the nearest bushes. The ground is pink with fallen cherry blossoms. “It’s the smell,” I splutter. “I’m sorry. It’s not you. Don’t be hurt.”

He is though, a little. It’s in his voice when he says, “We’ll be together tomorrow at the hospital for the ultrasound.”

This does make me feel better. The nausea ebbs and I want to doze off, just for a short nap. Tomorrow after the appointment, we can go for lunch in town. Pizza, this time. Pizza with extra tomatoes.

Leila Aboulela’s latest novel, Lyrics Alley, was Fiction Winner of the Scottish Book Awards and short-listed for the Commonwealth Writers Prize. Her previous novels The Translator (a New York Times 100 Notable Books of the Year) and Minaret were both long-listed for the Orange Prize. Leila is a recipient of the Caine Prize for African Writing and her work has been translated into 13 languages. She grew up in Sudan, spent most of her adult life in Scotland, and now lives in Doha. To learn more, visit www.leila-aboulela.com.

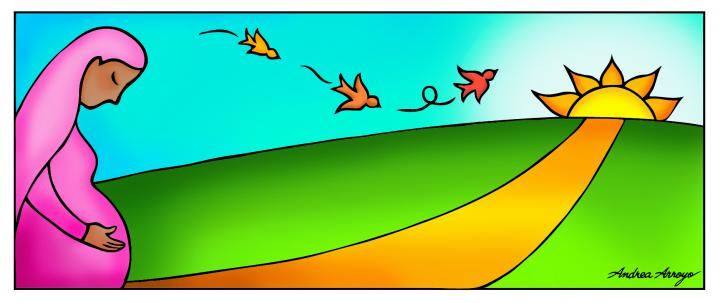

Illustration by Andrea Arroyo

Related Content

|

Samina Ali tells about her medically dangerous labor and delivery, during which she almost died, and what she learned from her infant son during her long period of rehabilitation. |

The organization, Migrantas, gives migrant women and mothers a platform to express their experiences as women in a foreign land. |

This photo series looks at a unique option offered by Washington State, USA to imprisoned mothers and their children. |

As a way to process and release the pain and anger around her traumatic labor and delivery, Renee Hoffman created this Cesarean Quilt. |